When it comes to a greener future, the vehicle we choose to get there really matters.

In July, amid Lockdown Five in bitterly cold Melbourne, I went online and made a very aspirational purchase. A brand new pair of boots were set to become mine, as I looked forward to making an entrance into my first in-person university class of my degree.

Of course, we all know how that went. The boots arrived… at the beginning of Lockdown Six.

I promise you there is a broader point to this, because I don’t want to discuss the boots – even though they’re very good – but rather how they got to me.

The boots were made (if the label is to be believed) in Portugal. But by the time I ordered them, they were in a U.K. warehouse of a notorious fast-fashion company, because yes, I am part of the problem.

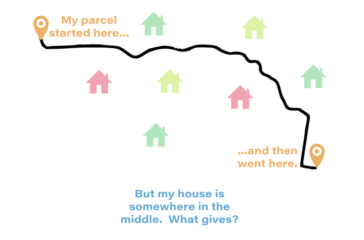

Australia Post took it from there, “manifesting” my parcel from the warehouse and driving it to the airport. My boots arrived in Australia 36 hours after take-off. The next stop was a sorting centre in Melbourne’s north, and from there they were driven to another hub in the city’s south.

There’s just one problem with that: they drove my boots past my house.

This isn’t a jab at postal workers, who are working under incredibly difficult circumstances right now. Nothing went wrong here, because I do live closer to the destination hub than the origin.

People who finished high school in Queensland should understand the issue Australia Post faces: questions asking students to find the most efficient route through a network of hubs are part of the Queensland Core Skills test.

The more specific the destination, the greater the challenge becomes. Originally, my parcel just had to make it onto a plane to Australia – benefitted by economies of scale. By the end, it had to be narrowed down to my house.

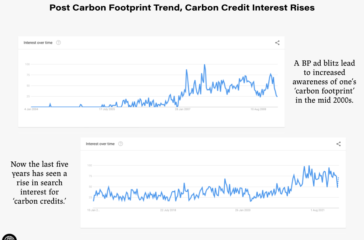

Those economies of scale also come into play when considering the environmental impact of my parcel. This impact matters to Australia Post, who buy offset credits to make their deliveries carbon neutral, offsetting over 200 thousand tonnes of emissions since the program started in 2019.

But the best carbon is the carbon never emitted in the first place. So, let’s look at the energy it took to get my parcel from the U.K. to my house.

At the beginning of its journey, the fuel consumption of my parcel was shared across all of the other packages on the plane. By the end, there were less parcels to share that same fuel burden across.

That means despite planes using so much more fuel than a parcel truck, the plane flight from the U.K. to Australia was more energy efficient than the truck drive between sorting centres.

And this isn’t theoretical thinking or a guess. The Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the U.S. conducts regular studies comparing the fuel efficiency of various modes of transport – from planes to cars.

They compared the total fuel consumed by all the trips of a given transport mode against the total distance travelled by each passenger. Here’s what they found:

Intercity rail – that’s trains that travel between cities – were found to be the most efficient mode of transport. Close behind is transit rail, comprised of both “heavy” and “light” rail – think the New York City subway or Melbourne’s tram system.

Surprisingly, motorcycles and planes are about equally as efficient. That’s because motorcycles are very light and don’t require much fuel, while the higher fuel needs of planes are dispersed among hundreds of passengers.

Cars are in the middle, followed by commuter rail. Confusingly, it’s defined as having “usually only one or two stations in the central business district” – so not quite on the scale of intercity travel but larger than a metro rail system.

One reason why commuter rail could be less energy efficient than its intercity and transit counterparts could be the energy it uses in the first place. Unlike light rail, which uses electricity, Oak Ridge say “most” of the 25 systems they analysed rely on diesel power.

Another gas guzzling mode of transport? Light trucks – think the Australia Post parcel truck used to cart my boots around Melbourne. In fact, a plane passenger can travel 14.23 miles further than a light truck passenger using the same amount of energy.

That’s 22.9 kilometres – more than a half marathon!

Diesel is also part of why buses are less efficient than cars in this analysis, which may surprise you. But the much bigger reason buses are less efficient than cars is that they have less passengers.

The U.S. Department of Energy explains: “Transit buses are not very efficient at their current ridership rates, where, on average, a given bus is less than 25% full.”

Let’s go back to the Oak Ridge report and look at the real numbers to see what impact that has on efficiency. In 2017, transit buses used 91.6 trillion British thermal units (Btu) worth of energy, compared to the 6,339.3 trillion Btu cars used.

But car passengers travelled 2.2 trillion miles, compared to just 20.2 billion (note the ‘B’ there) miles travelled by bus passengers. This means bus passengers used 1.44 per cent of the energy to travel only 0.92 per cent of the distance car users did. Ouch!

But bus users still have an edge over the least efficient use of energy by far: the somewhat murky ‘demand response’ category. Even if you’re not clear on what that means, you’ve likely travelled this way, as demand response includes taxis and rideshare.

They’re the least efficient way to travel because demand response drivers use energy in order to get to a passenger before actually transporting them. Buses may transport more refrigerated air than passengers in the U.S., but they spend less time completely empty.

So, there’s the numbers. The road travel leg of my boots’ journey to me was more logistically complicated and energy inefficient than the air travel leg. But you might have a question about that: why does it matter?

The unfortunate truth, as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change informed us last month, is that humans have been having an “unequivocal” impact on the environment, and transportation is part of that impact.

And for the Federal Government, saving carbon means more money from continued foreign investment. On ABC TV’s News Breakfast, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg spoke about the importance of net-zero emission targets to Australia’s economy.

“I certainly see it in our interest being part of these global agreements,” said Frydenberg. “Financial markets have always factored in these significant structural shifts.”

But for now, the energy used to make our cars, planes, and trains go has to come from somewhere. And as we’ve already discussed, diesel is the source of energy for some of our public transport options.

Even electric transport – electric cars or light rail – aren’t as green as they could be right now. That energy, more often that not, can have an inconvenient source, too. We’re still a ways off from solar-powered trains.

But those numbers from the report we’ve just looked at, do show how public transport could be a big part of the planet’s journey to net-zero, as well as reveal a huge problem it faces.

Public Transport is Sooo Pre-Covid

We’ve actually already touched on the problem facing public transport. It’s those pesky numbers that show buses are more energy inefficient than cars.

That shouldn’t be the case; economies of scale should disperse the higher energy use of buses over the greater number of passengers they take. But in the United States, there aren’t enough transit bus passengers to offset the increase in energy use.

So, how many more passengers would it take for buses to tie with cars, not beat them? Let’s use that 25 per cent passenger figure from the U.S. Department of Energy as a starting point; they said it was less, but they didn’t provide any additional information, so as far as I’m concerned that’s on them.

We know that bus passengers currently travel 0.96 per cent of the distance car passengers do, but use 1.44 per cent of the energy. To make passenger miles match energy use, it needs to increase by 1.57 times.

That’s a passenger increase from 25 per cent to 39.25 per cent. To get there, every two current bus passengers would need to convince one friend to ride with them.

Of course, this would also make the bus heavier and use more energy. However, a 2018 study published in Springer’s Transportation journal shows overall energy efficiency increases as bus occupancy rises – the distance the new passengers travel outweighs their additional weight.

The study analysed the fuel efficiency of different occupancy levels of four different bus models, comparing the amount of energy used per passenger kilometre travelled. It found the average full bus used about a quarter of the energy per passenger kilometre compared to a 20 per cent full bus.

That’s a huge energy saving that would certainly put buses above cars, and maybe even planes, in terms of efficiency. There’s just one problem, it’s clear, at least in the U.S., that people don’t really like buses, or any public transport at all.

Back home, we face similar issues. The Australian Bureau of Statistics found 14 per cent of Australians used public transport in March this year, down from 23 per cent pre-Covid. One in six people who used public transport regularly before the pandemic haven’t used it at all since March 2020.

It doesn’t look likely public transport use will return to normal levels once restrictions ease, either. 61 per cent of people the ABS surveyed said they don’t expect their current habits to change.

For some who’ve stopped or reduced their public transport use, they may be working from home. But for others, public transport may not be an attractive option, and that may have been the case pre-pandemic.

It’s an issue that’s created some unlikely advocates. The Head of Public Policy for RACQ – that’s right, the car insurance company – called on the Queensland Government to act last year. Dr Rebecca Michael said “we need to do everything we can to encourage more sustainable transport”.

Michael’s concern is the increased road congestion created by more drivers on the road. She’s advocated for an integrated public transport authority to be created in Queensland, which would tackle issues around service reliability, frequency and affordability.

But there’s another issue passengers face before even getting on the bus, and that’s getting there in the first place.

The Last Mile Problem

Earlier we discussed how the last leg of my online shopping’s journey to me was the most logistically complicated part of it. There’s a name for that phenomenon in the postal world: the last mile problem.

DFDS, a major European shipping and logistics company, says “the main challenge of the last mile is to handle low-density deliveries cost-effectively.” That’s because the last mile of a journey is by far the priciest; 53 per cent of delivery costs come from the last mile.

One of the causes should be familiar by now: the DFDS Scandinavia Vice President Niklas Andersson says “delivery trucks and vans are too often half-empty when they make their rounds”.

“The current situation simply isn’t environmentally sound,” he added. “We can’t continue to compete on price and delivery times without hurting the environment in the long run.”

But the last mile problem isn’t unique to shipping. The distance between a bus stop or train station and one’s home or workplace can also create friction for public transport users. For some, it’s a pain point that leads them not to use it altogether.

For example, unless someone’s lucky enough to have a bus stop or train station near their home, the walking distance could be a deal breaker. When you’re coming home from a stressful day at work, the last thing you want is more surprise exercise.

Former Queensland Deputy Premier Jackie Trad was invested in this issue. She oversaw Brisbane’s Cross River Rail project, which involves building several new train stations around the city.

In March 2019, the locations for these stations were announced, including one near an investment property Trad had purchased a week before the announcement. Trad didn’t formally disclose the purchase to Queensland Parliament in the required time-frame, leading to corruption allegations from the state opposition.

The Liberal-National Party referred the issue to Queensland’s Crime and Corruption Commission in July. Three days later, Trad rang Commission chairman Alan McSporran to “self-refer” the matter.

“There’s no compromising my integrity, I didn’t feel as if I was being influenced or there was an attempt to,” McSporran said at the time. He later recused himself from any further CCC investigations into the matter.

In September, the Commission announced “no evidence … supported a reasonable suspicion of corrupt conduct,” and didn’t launch an official investigation. “However, as a general proposition,” they added, “failing to declare and properly manage a conflict of interest creates a corruption risk.”

Despite this finding, Trad was removed from the project by Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk the next day. “The Premier has a right to expect the highest standards from all of her ministers and on this occasion, I did not meet those standards,” Trad told media.

Last year, Trad told Guardian Australia the matter – along with another CCC investigation into a different matter which cleared her of wrongdoing – was part of a campaign against her.

“There’s a concerted campaign against me because I guess I’ve stood up, I’ve stood up for the values my community care about and because there have been positive outcomes in that respect.”

Walking distance isn’t the only thing that can reduce the burden of the last mile. For people who live in outer suburbs where walking isn’t an option, adequate parking space can allow people to use public transport for a portion of their trip.

The train stations with the best carparks tend to be in marginal federal electorates, at least if former Infrastructure Minister Alan Tudge has anything to do with it. He oversaw the implementation of the Urban Congestion Fund, established in the 2018-19 Federal Budget.

The $4.8 billion fund included $660 million in funding for the construction of commuter car parks to ease traffic congestion. 40 sites for car parks were chosen in the first part of 2019, in the lead up to the federal election that April. Of those, 27 were selected the day before the election was called.

In June this year, the Australian National Audit Office released a report on the program. They found the selection process involved canvassing the MPs of 23 Coalition-held electorates, as well as Coalition Senators or candidates in a further six electorates held by opposition parties.

The result: 77 per cent of sites chosen were in Coalition-held electorates, with a further 10 per cent in the other six canvassed. 64 per cent were in Melbourne, despite the majority of Australia’s most congested roads being in Sydney. And most of Melbourne’s sites were in the south-east, despite most of the city’s congested roads being in the north-west.

The ANAO found the implementation of the Urban Congestion Fund was “not effective,” and criticised the selection process, calling it “not demonstrably merit-based”.

Alan Tudge denied any wrongdoing and said decisions were “made on the basis of need” in August. “33 of them were ticked off by the department before coming up for decision and we took those to the Australian people and the Australian people voted for them.”

So with bruised trust in both state and federal levels of government to tackle the last mile problem, the Brisbane City Council looked overseas for a solution.

Scooting to Net Zero?

“Please unlock me to ride me, or I’ll call the police.”

That was the threat made on many U.S. streets in 2018. The source: new e-scooters that quickly earned the ire of locals.

While these companies had launched before that, 2018 saw the rideable industry’s most rapid expansion. Scooter companies grew from five to 70 U.S. cities that year, entering the national conversation for the first time.

But not all of those conversations were good. The adoption of the “move fast and break things” philosophy of the rideshare industry by scooter companies put them in hot water with local governments. Four cities banned them altogether.

The business model of rideables also raised problems for disabled people. That’s because riders could leave scooters in the middle of footpaths when they were finished riding, making city streets harder to navigate.

This issue led to a lawsuit from accessibility advocates filed in 2019, who alleged the “uncurbed growth” of the rideables industry “comes at the detriment of the rights of all disabled persons … causing Plaintiffs injury, severe anxiety, diminishing their comfort and discriminating against them based on their disabilities.”

Four of the plaintiff’s claims were dismissed in 2020. A motion for class certification was denied in June this year.

In response to the poor initial entry in the U.S. market, European rideable company Lime took a different approach when entering the Australian market.

Brisbane was the first city in Australia to trial e-scooters in 2018, following consultation between the local council and Lime. When it comes to the last mile problem facing public transport, Brisbane City Council believes e-scooters could fill that niche.

In its draft e-mobility strategy, the council wrote “e-mobility options have potential to complement the role of public transport and provide short distance transport options within communities so people can conveniently access local services.”

“We could have said ’no’ to this technology, like other cities have done,” wrote councillor Ryan Murphy in the 2020 report, “but this would leave our residents and visitors worse off, with fewer options and less choice when it comes to getting around Brisbane.”

E-scooter programs have now expanded around the country, with trials now running in every state except New South Wales. State Transport Minister Andrew Constance ruled out a trial in March, branding programs in other states “a disaster”.

Constance’s claims aren’t entirely without merit. Last year, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission found Lime failed to disclose safety issues to riders. That’s despite knowing about 50 incidents, some of which resulted in broken bones.

Lime conceded they broke consumer law in a written statement to the ACCC, writing: “We are a young company and while we don’t always get it right, we learn fast.” The company pulled out of Brisbane completely in June this year.

Brisbane’s rideable market is now served by Neuron Mobility and Beam, who both secured three-year contracts in May. Both companies introduced e-bikes to their offering in July, replacing Brisbane’s CityCycle scheme that was scrapped last year.

So, can e-scooters and e-bikes get people out of their cars? Lord Mayor Adrian Schrinner is quietly confident, revealing in June that “between 30 and 50 per cent” of rideable trips were replacing car trips in the city.

For Neuron and Beam, their shareable business models appear to be safe for now. Personal e-scooters are on the market if you want to cut out the middle-man, but the lowest cost model is $999 from JB Hi-Fi. That’s around 22 months’ worth of monthly passes from Neuron.

As trials continue around the country, lawmakers and stakeholders are waiting to see if rideables can really take public transport users the last mile.