An MMP system would dramatically change Australia’s political landscape.

It was always going to be an unusual election. Nearly 70% of votes were cast in advance of New Zealand’s 2020 election, making for a quiet Saturday at the polls, with only 3 in 10 New Zealanders opting to vote in person this year.

Unlike in Australia, voting is not compulsory in New Zealand. Yet, voter participation reached a historic 21-year high of 82.5% of enrolled voters. This was despite the new and unique challenges of holding an election amid a pandemic.

However, the uniqueness of the lead-up to Saturday night’s election result paled in comparison to what transpired when the votes were tallied. (And no, I’m not talking about New Zealand electing what Newshub billed the “gayest parliament in the world.”)

For the first time in nearly a quarter of a century, New Zealand voters had awarded a single party majority control of the country’s parliament. Since the introduction of New Zealand’s Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) system in 1996, many had considered this impossible.

As a result of this, political parties would face protracted closed-door talks in the weeks after past elections to negotiate coalition agreements. Multiple times, party leaders have turned to far-right minority party NZ First leader Winston Peters to serve as a “kingmaker” of sorts, as Jacinda Ardern did in 2017. But on Saturday, Winston was out, and Jacinda Adern was in.

But why did minority parties hold such great power in New Zealand’s parliament for so long? The country’s MMP electoral system is a big part of the reason. And, it turns out that the MMP system could be much more representative of voters’ intentions than those in Australia or the United States.

As voters in the Australian state of Queensland and the United States head to their respective state and federal elections in the next fortnight, how do their electoral systems stack up, and are their voters missing out?

What Does Mixed Member Proportional Mean?

In the early 80s, trust in New Zealand’s electoral system was extremely low. Voters felt that the country’s First Past the Post system created parliaments vastly different to what they wanted, and the system concentrated power too heavily between the major Labour and National parties. In 1985, a Royal Commission into New Zealand’s electoral system was established. When the Commission concluded in 1986, it proposed what was considered to be a radical recommendation at the time: set up a MMP system to determine the government.

The Royal Commission proposal involved increasing the size of New Zealand’s parliament to 120 MPs. Half of the members would be elected in conventional geographical electorates, and the other half would be selected from a list of members made by each party in order of preference. The national vote share a party gets would be used to determine how many members they have elected to parliament. If a party did not win enough electorates to match the total seats they were entitled to, the party would be allocated list seats to top up their total share. This way, every party would have proportional representation in parliament.

The leaders of the major parties did not welcome these recommendations, as both benefited from the current electoral system. However, both ended up promising to hold a referendum on the recommendation from the Royal Commission, with neither intending to uphold this promise.

When the National party won the election and did not follow through, voter confidence was at an all-time low. Polling at the time showed that people respected politicians as little as used-car salespeople. So, in the early 90s, the government held two referenda on the issue, and implemented the MMP system in 1996. Today, MMP functions largely the same as what the Commission proposed back in 1986. Voters in 72 New Zealand electorates (7 of which are Māori electorates) receive two ballots at each election. One ballot is to vote for the representative of their electorate, and one is a party ballot to determine each party’s share of the remaining 48 list seats up for grabs.

How Do Australia and the U.S. Compare?

In Australia, we use several systems to elect our representatives. In the lower house, we use preferential voting to elect MPs in geographical electorates. This allows voters to put minor parties as their first preference, but not “waste” their vote as it can still flow through to a major party.

In the upper house, this same preferential system is used, but similarities to New Zealand’s party list system are present. If voters choose to vote for parties instead of candidates on their senate ballot, parties then distribute that vote to their candidates in order of party preference.

READ: AUSTRALIA’S ELECTORAL SYSTEM ISN’T THE ONLY THREAT TO AUSTRALIAN DEMOCRACY. FORMER PM KEVIN RUDD SPEAKS OUT ABOUT MEDIA MONOPOLIES.

However, the geographical nature of Australia’s electoral system still puts minor parties at a disadvantage. Parties that get a minority of the vote are unlikely to get proportional representation in parliament, but rather none at all. This is because geographical borders separate support for minor parties between electorates and votes cannot coalesce.

Some argue that Australia’s system of government is also much less stable than in New Zealand. By 2018, Scott Morrison had become our sixth Prime Minister in 11 years. Morrison has still not exceeded the time in office of his predecessors Julia Gillard, Kevin Rudd, or Malcolm Turnbull.

Appearing on New Zealand radio at the time, Labour MP Michael Wood said: “People have often criticised MMP saying it would lead to instability — actually we’ve had incredibly stable Governments, and I think that’s something to take note of and feel good about.” This comment aged like milk: he appeared on the program alongside National MP Judith Collins, who currently serves as the party’s third leader this year.

However, Australia’s system is still much more representative of voter intentions than the First Past the Post system that is used in the United States. There, many voters register with a party to take part in the primary process. This allows state legislatures to draw district boundaries that deliberately suppress support for a party across many electorates or concentrate votes in just a few. The United States is also not a democracy, but a constitutional republic that uses an Electoral College to decide the winner of elections. This means that all votes are not equal, the value of one’s vote is contingent on where they live.

Even though Australia’s system is not as representative of voter intentions as New Zealand’s, it is certainly not as bad as the system in the United States, right? After seeing what our parliament would look like if MMP were used at our last election, you may no longer agree.

The Impact of MMP in Australia.

To see what our parliament would look like if we used MMP in Australia, we first must make it a bit bigger. 40% bigger, specifically.

In New Zealand, 40% of the seats in their parliament are list seats filled by members who do not stand for a geographical electorate. To make Australia’s parliament match, we could wipe out 40% of the electorates in the country, but deciding which to remove would make this exercise way too complicated. If we did though, I reckon we could do without New South Wales.

So, our formerly 151-seat parliament is now made up of 251 MPs. To establish a baseline, let’s increase the representation of each party by the same amount to see what that would look like. Of course, we can only do this where possible: the representation of independent candidates cannot scale up unless someone invents human cloning. Due to rounding issues, the allocation of one seat cannot be determined. So, meet Australia’s new 250-member parliament:

Here, the Liberal-National Coalition is still our government, but that is because we have not applied an MMP model to Australia’s votes in 2019. So now, what would our parliament look like with that system: keeping our current 151 electorates the same and adding 100 list seats?

Before I show you Australia’s new parliament, I need to explain two more factors of New Zealand’s MMP system. Firstly, parties must meet a minimum threshold of votes. To be represented, parties must get 5% of the vote to get list seats or win one geographical electorate.

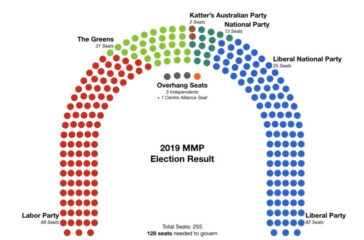

Secondly, if a party wins more geographical electorates than total seats they are entitled to, they keep the seats they have won but are given no list seats. The electoral commission adds on the seats above their proportional share on to parliament as overhang seats so that other parties still get the number of seats they are entitled to. Both factors are present in Australia’s new MMP parliament below:

Here, we have four overhang seats for independent members and the Centre Alliance, but the big shock is a change in leadership. Now, no major party has enough seats to form government on their own, and the more likely government here is a Labor-Greens coalition. If Australia used an MMP system, we would have a completely different government right now. In particular, the share of power for the Greens is much more representative of the 12.2% of voters who support them.

Making Your Vote Count, No Matter the System.

At the end of the day, it looks like Australia and New Zealand are not so different after all. On Sunday, Jacinda Adern kept the option of a Labour-Green coalition on the table even though she has a historic single-party mandate, and it looks like we would get the same result here in Australia if we used New Zealand’s electoral system.

However, electoral reform is far from a priority in Australia right now, and it is certainly not happening in the United States during an election-in-progress. So, with Queensland voters heading to the polls starting this week, and United States voters gearing up for a November election, how can they maximise their votes in the system they have?

LISTEN: HAVE QUESTIONS ABOUT HOW TO MAXIMISE YOUR ADVOCACY? SEASONED CHANGEMAKER TIYANA J HAS ALL THE ANSWERS ON THE CHANGEMAKER Q&A PODCAST!

In Queensland, preferences are your friend for two key reasons. If you align with the policies of a more niche minor party rather than those of the major parties, putting a minor party as your first preference means you can still support your preferred major party if your first choice doesn’t win.

But secondly, state elections are your chance to make a free-of-charge political donation to help advance the policies you believe in, just by filling out your ballot. Every election, the Electoral Commission of Queensland supplies public campaign funding to each party based on how many first preference votes they get.

This year, parties will receive $3.14 in funding for each first preference vote that goes to one of their candidates if they get at least 6% vote share. (A bill was passed that was supposed to increase this to $6 per vote, but this is not yet reflected in ECQ policy documents.) You might think that is a small amount of money, but for every party that gets over the line, the minimum payout is $525,362.44 in funding.*

So, even if your first preference candidate won’t win their race, you can support their next campaign and help them create more public awareness of the policies that are important to you. This is a particularly important mindset for voters in the United States to have, as they have less measurable control over their system.

In the United States, you cannot use preferences to make sure your vote is not thrown away, but you can participate in the primary and caucus process. By supporting single-issue candidates who are not necessarily viable moderate candidates, you can signal to the eventual party nominee the issues that they should incorporate into their platform.

For example, Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, and Andrew Yang’s championed policies such as public healthcare and universal basic income throughout the Democrat primaries this year. Now many have been discussed with Democratic-nominee Joe Biden’s campaign, and have much wider awareness and broader support than ever before.

And, of course, making change does not stop on election day. Regardless of where you live, what system you use to vote, or what change you want to see in the world, the real work starts the day after election day.

Getting to know what makes your local member tick and contacting them with your concerns is a valuable civic tool in your Humanitarian Changemaker toolkit. Perhaps those who are newly invested in the issue of electoral reform could start by sending their MP this article.

The Queensland State Election is on the 31st of October. Enrolled residents can vote at a polling place on that day. Or, they can vote from today at early voting locations, by post, or over the phone. Go to ecq.gov.au to find voting information, the health measures taking place to keep you safe, and more.

The United States Presidential Election is on the 3rd of November. Some enrolled citizens may vote at a polling place on that day. Voting eligibility, regulations and deadlines vary by state. Go to vote.gov to find out how, where and when you can vote. Go to eac.gov to report instances of election fraud

*This amount of funding was estimated by taking Queensland’s voter enrolment as of June 2020 (3,330,589 people) and adjusting it by the turnout at the last state election in 2017 (~83.7% participation). It is estimated that up to $9,631,644.79 in public funding will be awarded this election cycle. The theoretical maximum is $10,458,049.46 given 100% turnout, no informal votes, and all contesting parties reaching the 6% vote share threshold.