Policymakers and racial justice activists came together to discuss decolonising aid. Here’s what happened…

Earlier this year, dozens of senior policymakers in humanitarian response gathered virtually to discuss “decolonising” an international aid sector accused of being top-down, unaccountable, and – in some cases – racist and with unhealthy levels of power over the people it serves.

It had been nearly two years since the murder of yet another unarmed Black man in the United States sparked a global conversation about race – and the aid industry was not exempt.

A senior representative of a multilateral donor institution in the room raised his hand. His question came across as naive, but was, I suspect, intended as a provocation.

“I haven’t heard [the term decolonisation] in the [Global] South; I haven’t heard it here in Europe; I haven’t heard it with our colleagues in the United States or in Canada. I haven’t heard it from NGOs. So the question is… to whom is it a concern? What is the pertinence of it? Do we believe that something is wrong in the approach we have?”

He and more than 50 representatives of governments, foundations, UN agencies, international NGOs, as well as local humanitarians, aid funding innovators, and racial justice activists had been convened in February by The New Humanitarian for a private conversation to answer that very question.

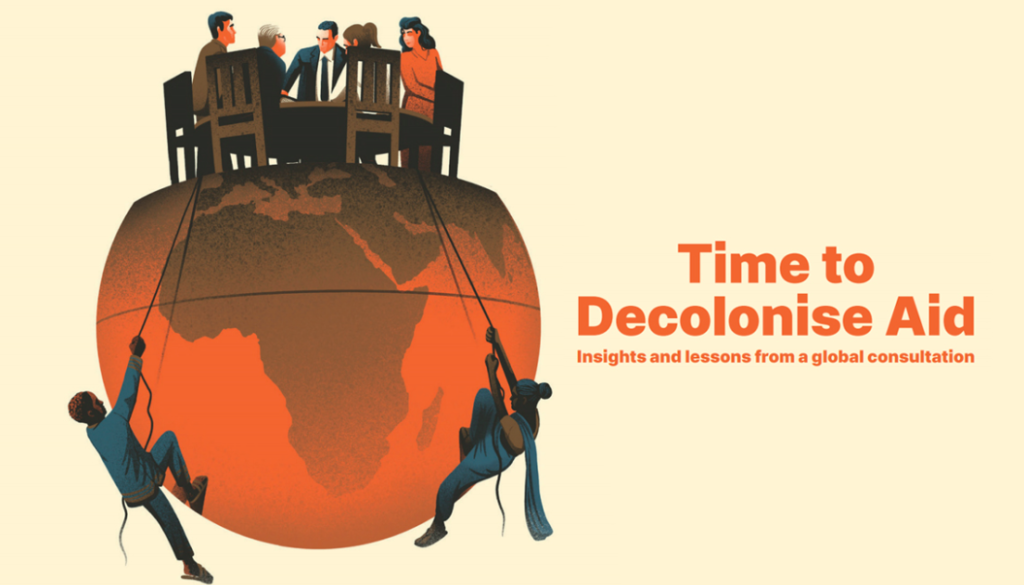

The frank and lively discussions that ensued made one thing clear: There are two dominant – and arguably mutually exclusive – schools of thoughts on decolonising aid. Whether they can be reconciled will determine whether and how any reform agenda will take shape. And this tug-of-war could, potentially, decide the future of aid.

The backdrop

By early 2022, the topic of race – and of “decolonising aid” – had become all the buzz across the sector: Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) dubbed its annual congress, “Exposing power and privilege in times of crisis”; the Centre for Humanitarian Leadership conference showcased, “the people we don’t see; the voices we don’t hear”.

But many people were still asking: What does decolonising aid actually mean? How should we go about it? And while it was a popular issue among practitioners, it was still largely overlooked – some would say actively ignored – by policymakers. When it was introduced for the first time in a donor forum in December 2021, one of the first reactions from a Western government was to deflect blame: “How about the Chinese?”

The New Humanitarian’s convening – held behind closed doors and off the record to give participants the space to speak freely – offered a rare opportunity to bring two worlds together: those controlling and spending millions of dollars of official development assistance and philanthropic funds; and a cadre of people extremely critical of the aid endeavour.

*/

-

The key takeaways

- There’s both support for – and concern around – the term “decolonisation”.

- But there’s no agreed definition of decolonisation in the context of aid: Some see it as more equitable ways of channelling assistance; others see it as ending aid altogether.

- Those in the first camp insist that aid is fundamentally good and reject more aggressive definitions of decolonisation. Those in the second see aid as harmful and even exploitative. Despite a willingness to engage and a desire for continued conversation, some areas of disagreement may prove unresolvable.

- One of the key challenges to decolonising aid is entrenched power dynamics – including the denial of structural racism and resistance to change in the North. Other challenges are rooted in the Global South’s own inability – or unwillingness – to take power.

- Quick fixes are unlikely to solve a deep historical problem; institutions who want to decolonise will need to commit to a long process.

In the lead-up to the convening, the lack of trust between the two sides was already palpable.

“It is fascinating that [these donors] accepted to come,” one proponent of decolonising aid told me ahead of the event. “They don’t know what’s possible in a conversation like this,” he said, suggesting that it would likely be more hard-hitting than donors expected.

Many civil society activists needed to be convinced that donors and policymakers were approaching the conversation with goodwill. One wrote in a survey circulated ahead of the meeting that she wanted to understand the appetite for “real change” among those who hold power in the sector.

And so it was in this context that the donor representative asked his question about the relevance of the decolonisation debate.

His comments were quickly and robustly rebuffed by many, including one representative of an international NGO who noted: “The UK supporter base for international NGOs is built on making our white public feel like they’re saving Black and brown people in the former colonies. In the international aid sector, we haven’t had our decolonising moment yet.”

Another civil society leader suggested funders ask themselves questions about the origins of their wealth: “Where did your money come from? Who was harmed in the process? What responsibility do [you] have to repair that?”

The subsequent exchange lasted four hours.

It was at once angry and optimistic; concrete and philosophical; but it may just have created openings among some participants to see things differently.

As one civil society leader said: “I don’t think many of the donors attending heard this straight… before. They can’t unhear what they [have now] heard.”

Many participants seemed hopeful that the topic was finally being taken seriously by those in power. But despite a clear willingness to listen, share, and look for ways forward, there were also clear tensions that will undoubtedly prove hard, if not impossible, to resolve.

Decolonisation: Two camps

Ahead of the meeting, a survey had been circulated to participants asking – among other things – for their definition of decolonising aid.

Many gave answers you would expect – addressing power imbalances (“a process of remaking power relations”); engaging in fairer relationships (“countries in the Global South should be informed, not controlled, by the Western architecture”); increasing local agency (“centring communities who are most directly affected”); and changing mindsets (“not approaching our grantmaking from a saviour mentality”).

But a smaller group of respondents saw decolonisation very differently.

“Stop considering this money as aid and reframe [it] as overdue compensation for already rendered services,” one of them wrote (for more on aid as reparations, check out this speech by Uzo Iweala).

Aid that is more locally led and inclusive is “not decolonisation”, this participant said. “That’s optimisation of a bad situation.”

A technical vs. moral conversation

There were basically two different conversations happening at once: a technical discussion about how to make aid better, and a moral conversation on how to address the wider geopolitical power dynamics that led countries to be in need of aid in the first place.

“Philanthropy should end. That is what decolonisation is,” one participant from the international aid sector wrote in the survey. “The world I would love to see in the future is that international NGOs don’t exist. The fact that we exist is a by-product of systemic problems.”

Presented with this point of view, the institutional players in the room were taken aback.

“There is a lot of anger in the room, which I understand,” one UN representative told the convening. “But it needs to be balanced with the recognition that… humanitarian aid has saved millions of lives.”

“I came to this conversation to understand how we as a government can deliver humanitarian aid in a better way,” a government official told the group. “I’m distressed by the flat rejection of philanthropy by the previous speakers because I don’t think it is consistent with something that’s fairly basic in human nature, which is the idea of standing shoulder to shoulder with other members of the human race.”

“It’s not about how to do [international aid] better, but do you need to do it? And do we [in the Global South] want you to do it?”

“In Africa, we are still a source of extraction – and that is by design. Our countries would not need aid if we could trade at the same level as Switzerland or Holland.”

“I am a little bit uncomfortable about the blanket refusal that I hear – that aid is inherently bad.”

“Philanthropy is the desire to promote the welfare of others – that is an important thing.”

Several civil society leaders pushed back, noting that aid is often influenced by the foreign policy interests of the donor country; that philanthropy involves billionaires making decisions on behalf of others with no accountability; and that intention doesn’t matter when the result is “not helpful at best and harmful at worst”.

As the conversation continued, some activists became frustrated by those seeking to defend the humanitarian enterprise.

“This happens every single time: We spend most of our time trying to dance circles – [we say] ‘let’s not call it colonialism; let’s call it something else’ – because it makes us uncomfortable and… if you acknowledge the coloniality of aid, it puts a moral burden on you to resist it.”

And yet for donors who have money to spend, this moral conversation about racism and geopolitics left them feeling lost.

Many donors in the room didn’t see as much value in working through messy, historical questions with no clear resolution and were impatient to get to concrete solutions and ways forward.

“I’d rather focus on tangible goals and necessary actions than on constraints,” the CEO of a philanthropic foundation wrote in the survey circulated ahead of the discussion.

“If we need to put 200 million tomorrow into [the conflict in Ethiopia’s] Tigray [region], what is the mechanism for that to happen that takes all these [ethical questions] into account?” the government representative quoted earlier asked the group. “That is the reality in the pragmatism of what I’m dealing with. It’s as simple as that.”

‘A healing journey’

However, for many civil society leaders, talking about the larger historical problem was an essential part of the solution.

“We have to come to terms with what has happened in the world and all the different countries where we’re working,” one of them told the room. “Until we actually grieve that and we face the truth, we’re not going to get to a place to be able to repair that in a very authentic way… This heaviness and the discomfort that we’re experiencing here… is the start of what I would call decolonisation [and] may be the start of a healing journey… We’ll figure out the other [technical] stuff [about how to move the money] later.”

“We have to come to the acknowledgement that our institutions have been a part of that problem and we have to grieve that.”

“We’re coming at it from a professional point of view, not an aggrieved race point of view.”

Another foundation representative insisted that the conversation about decolonising aid needs to be placed in a wider historical context.

“This is really part of a longer centuries-old struggle of people who have been colonised, who have been enslaved, and who continue to struggle against that and seek allies and seek a reimagining of the world order – a radical reimagining of global economic governance, of global political governance, of which humanitarian aid, development aid, civil society actors, and philanthropy are part of.”

Institutions were told they needed to resist the pressure to be driven by knee-jerk reactions and the search for quick solutions that tick the boxes without doing the hard work.

“We need to acknowledge and agree the depth of work that needs to be done to achieve the change that we say we want. Those underpinning issues of racism and racial equity, those things that underpin colonisation, need to be discussed, and we’re not there yet,” said one racial justice advocate. “I have a question for the institutions who are in the room: Are you equipped to have these deep conversations?”

The answer, for many, it seemed, is no.

“I hadn’t really understood and appreciated the big picture, the anger, the anti-aid movement, the strong anti-North perspectives,” the CEO of another philanthropic foundation told me after the event. “I have never been much exposed to that.”

One civil servant described the meeting as “probably the most irritating, frustrating, stimulating, fascinating conversation that I’ve had for a few years”.

Obstacles to decolonisation

We asked participants what is getting in the way of decolonising their work.

Several participants raised challenges I haven’t heard discussed in the mainstream discourse, linked to the role of the Global South in decolonisation. One described the “failure of imagination” on his native African continent “in understanding and using the power we have… to build a system that doesn’t involve ‘their’ rules.” Another reiterated this when she wrote: “The flip side of sharing power is taking up responsibility and mutual accountability, and I’m not sure we’re seeing it yet.” A third wrote: “Civil society organisations in the Global South have to become a force to reckon with.”

On the other hand, Westerners pointed to fears around the lack of civil society space in the Global South. One foundation CEO questioned the political space available within countries that receive aid for community-based organisations to operate freely. One Western government representative pointed to the need to ensure that human rights standards are maintained in a decolonised humanitarian aid system, especially in societies where women’s rights are not enshrined and respected.

Others cited more commonly referenced legal, administrative, and logistical obstacles, like constraints imposed by parliaments that make it harder to channel money to local actors; donor attitudes towards fiduciary risk; perceived lack of capacity at the local level; and the challenges of finding strong local partners who can work at scale and/or southern intermediaries who do not become gatekeepers.

Still others pointed to entrenched power dynamics – including territoriality and competition for resources, denial of structural racism, and resistance to change. “The institutions that hold power [have not] grasped the necessity of this work,” one participant wrote in the survey. “Or they are not interested in it yet because it challenges the status quo.”

Some participants also cited obstacles that may sound more mundane but could make all the difference: the lack of a common definition of decolonisation (“it is not entirely clear what is part of the ‘agenda’ at this point”); and the need for clear metrics (“everyone is so busy; unless you make this a true goal and objective, it won’t happen”).

Finally, some noted that “dichotomous thinking” makes people feel defensive, and that the debate can often descend into a “prosecutorial mindset” rather than an inspiring vision of success.

Is decolonisation the right term?

Most participants who filled in the survey supported the use of the word “decolonisation” in the context of aid, arguing that “we need to call things by their name”.

But some felt it was needlessly confrontational and didn’t necessarily help drive towards a solution: “It helps stimulate the debate, but I don’t know if it helps make the debate focus on an objective that everybody can agree on,” one multilateral agency representative said.

“[The term ‘decolonisation’] takes the bull by the horn; we cannot afford to wash over the issue.”

“As a country with a colonial history, using this term has more impact and clearly refers to power imbalances, racism and western approaches.”

“It basically divides up the world into the bad guys and the good guys.”

Yet others worried the term may be counterproductive because it would never fly in certain political circles. Pursuing a similar approach but calling it something else might allow it to gain more traction, one government representative said.

A minority of participants – from the North and South alike – felt the term had been co-opted. “Many of us in the South do not agree with or relate to this terminology,” one wrote in the survey. “In fact, we see it as a further imposition of a white saviour complex, with the powerful West once again deciding what is good for us and how this must be done.” One Western donor said he found the term “righteous and condescending”.

So what might be more appropriate?

To avoid the polarities of “us vs. them” thinking, one participant suggested using the term “post-colonial” instead. “It invokes the history of colonialism and the fact that it’s very much present in many parts of the world, and it allows us to think beyond that historical era about what we can all do to create a post-colonial future.” (See this article for more on post-colonial framing.)

Where does the conversation go from here?

My sense from moderating the discussion was that many in the room – on different sides of the debate – were willing to be honest and vulnerable. Answers to the survey, including by bureaucrats, were detailed and thoughtful.

Former colonial powers owned up to their past. Donors recognised the inherent tension between shifting power and being an agency of foreign policy. One government respondent noted the harm of its approaches around sanctions and counter-terrorism.

Leaders of international NGOs also acknowledged the hard work ahead of them. “I am trying to overcome a lot of attitudinal barriers,” said one. “Many of my colleagues do really feel that we’re doing excellent work; we’re saving lives; we need to maintain the integrity of that operational added-value to these vulnerable communities… They’re not quite ready to have the conversations with the language you might use here.

“But that’s not to say that with time, and with the activist voices, they can’t get there. So, my attitude is: We need to take that voice, that pressure, the anger, the disappointment, the frustration, and harness it into something that we in positions of responsibility commit to doing.”

There was also a clear desire for continued conversion – from donors and civil society alike.

“I’ve learned a lot,” one government representative said. “I’m keen to continue this conversation and engage in this dialogue with a bunch of you.”

“Relationships are the resolution,” one community activist said. “By us continuing to talk, committing to sit together, we will find the answer.”

“I have never been in nor seen a meeting like that, specifically with institutions, government representatives, and donors there in numbers,” one racial justice activist said after the meeting. “That was a first, and I have to say it felt more meaningful than other meetings I’ve been in… there could be something very special in that whole group. We create real change when people commit: commit to holding spaces, commit to showing up, commit to collaborating and to taking action, together.”

So the question to me is how to reconcile the two objectives at play: making aid better and ending aid altogether. Can these two realities exist in parallel?

Some in the room felt it was possible to work on both fronts at once.

“It’s important to engage in, and be stretched by, this debate [about the broader power dynamics] – AND to do our work [within existing systems] better as we stretch,” the CEO of one philanthropic foundation wrote in the Zoom chat as the discussion heated up. “Otherwise we may fail to be stretched, AND not make very important improvements to the flow of funding towards those close to the problem.”

Others were more sceptical.

“Your observation that both sides will probably have to exist together sort of defeats the purpose because both sides are saying two different things,” one civil society leader responded in the chat.

“Your priority is the flow of money. For us, it’s not (just that). It’s about having the autonomy to decide for ourselves.”

“This is about making sure we can address the humanitarian needs in the world, while recognising that we are living in a neo-colonial era with all these power imbalances.”

As the meeting came to a close, one participant tried to close the gap.

“There is a huge tension in my mind that I walk every single day around the political, aspirational, moral imperative of changing the system as opposed to the reality of incremental changes that need to happen because people are not ready for those more radical, moral decisions,” said the activist, who works with institutions in the humanitarian system to help them evolve their ways of working.

“And I sometimes feel like I’m a hypocrite… But I’ve come to this understanding that while we need to push the donors and our civil society sisters and brothers in the North to do better to act better and to prioritise the moral imperative, we also have to accept the realities of the current barriers and problems that they’re facing to change, and we have to find some solutions to that.”

Edited by Andrew Gully.