🎧 Shifting Public Opinion: responding to the IPCC report

The sixth assessment report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) does not make for a particularly uplifting reading— You have probably seen headlines about “code red”, “unequivocal human influence” and 1.5C of warming by 2030. As Changemakers it’s up to us and the rest of civil society to turn the dread and horror from the report into determination, effort, unprecedented cooperation, and visionary commitment.

It would mean making profound changes in our societies, economies, our ways of doing things. But it is possible to do. And we know how to do it. Scientists, policymakers, and experts of all kinds know what the solutions are to reducing our global greenhouse gas emissions.

Perhaps the biggest obstacles that stand in the way of adopting these solutions are actually interconnected personal or political challenges. There’s a lot of money that goes into the fossil fuel industry, which is why there is so much resistance from leaders to changing the status quo. And without significant public interest and pressure in transitioning to a more sustainable future, there is little incentive for government or big business to do so.

So what needs to change?

The solution to getting governments and big businesses here In Australia to start taking action, is to use direct action, strategic campaigning, and community organising and mobilisation tactics to shift the current power imbalance that exists— we want to shit the power to the people, and if enough people, put enough pressure on governments and corporations to act— they inevitably will… history has shown us this. From women’s suffrage to the contemporary feminist movement, From the civil rights to the BLM movement, and other ongoing social movements advocating and campaigning for the realisation of human rights by demanding action… they’ve shown us that we can only get decision-makers to start taking action to change what is considered to be “business as usual,” When there is enough political pressure on them to do so.

The thing that I actually wanted to focus on in this episode is less about the need for activism to demand climate action, and more about how we can bring more people into the movement— because we need to have more people taking direct action, pushing these campaigns forward to shift the power from these big corporations and government leaders, to the citizens, so that decision-makers will be forced to act. More people = more power = more pressure = more likely to act.

When you consider the magnitude of the issue of climate change, and how it will affect or already is affecting every single human and non-human animal on the planet, as well as the natural world, it seems counterintuitive that not every single person is willing to take action and demand change. The reason not everyone is willing to do so is that not everyone cares enough about climate change— not necessarily because they are bad people, but because for whatever reason they haven’t formed strong enough opinions about the issue that will compel them to act. So the challenge is, how do we actually get more people to form a strong enough opinion about climate change that they feel compelled to act?

Now there isn’t much to debate when it comes to climate change— the science is clear, and there is consensus from the overwhelming majority of at least 97% of climate scientists about the science behind climate change, so it’s not an issue of convincing people to believe in climate change— if people don’t believe the world’s leading thinkers on this topic, we have little chance as activists of getting them to believe the science.

What we need to convince people of, is the need to care about climate change enough to take action. Public opinion plays a significant role in how the government and other actors respond to demands for climate action. So, shifting public opinion is key.

Components of public opinion: attitudes and values

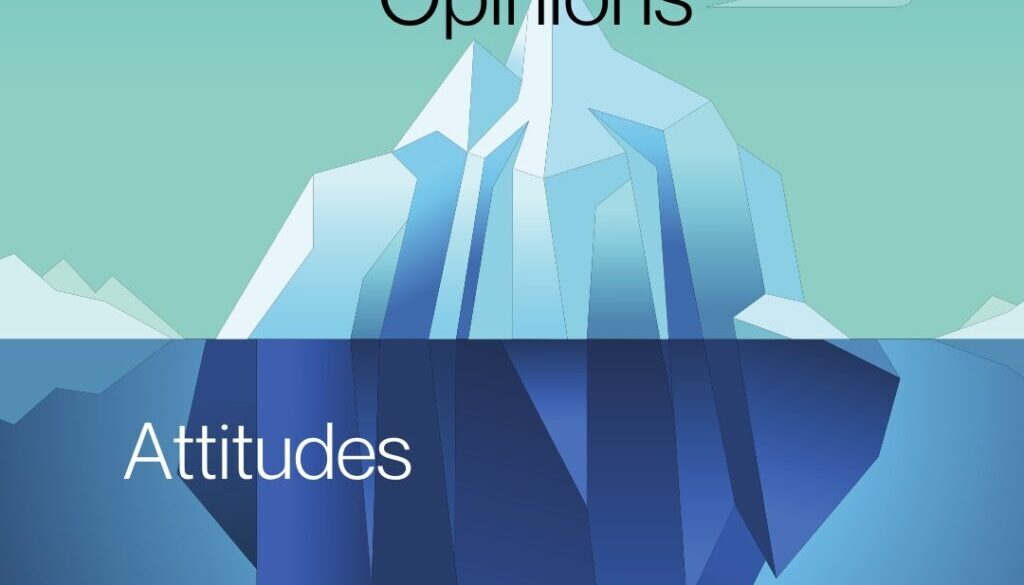

How individuals form opinions and the types of opinions they form depend on their immediate situation, more general social and environmental factors, and also their pre-existing knowledge, attitudes and values. Public opinion is shaped by 3 stratified factors held by individuals; opinions, attitudes, and values.

Most famously characterised in public opinion research by Robert Worcester; opinions are “the ripples on the surface of the public’s consciousness—shallow and easily changed,” attitudes are “the currents below the surface, deeper and stronger,” and values are “the deep tides of public mood, slow to change, but powerful.” According to Worcester, the most important concept in public opinion research is values, which determine whether and how people will form opinions on a particular topic; people are generally more inclined to form an opinion when they perceive that it aligns with their personal values. Values are adopted early in life, shaped by an individual’s upbringing, family and friends, and cultural context, and are not likely to change, but rather strengthen as people grow older.

Once an issue is identified, some people will form attitudes towards it, and as these attitudes are expressed to others by sufficient numbers of people, a public opinion on the topic begins to emerge. Not all individuals will develop a their own attitude about an issue, if they don’t care about it or know enough to develop an attitude.

Therefore, a seemingly homogeneous body of public opinion may therefore be composed of individual opinions that are rooted in very different interests and values. If an attitude does not serve a function such as one of the above, it is unlikely to be formed: an attitude must be useful in some way to the person who holds it.

Factors influencing public opinion

There are a number of factors that can influence and shape public opinion. Environmental factors play a critical role, and are key for the development of both opinions and attitudes— including their family, friends, workplace, religious community, or school. Individuals will often adjust their attitudes to conform to the most prevalent groups that they belong to.

Mass media and social media also play a role in affirming latent attitudes and ‘activate’ them, prompting people to take action.

Interest groups, such as NGOs, religious groups, or unions also cultivate the formation and spread of public opinion that might be of concern to their constituency. This can be done through mass media and social media, words of mouth, or through an organised advocacy or PR campaign.

Finally, opinion leaders can play a major role in influencing individual opinions— such as political or religious leaders.

Changing public opinion

The greater a person’s level of cognitive engagement with an issue, the more likely he or she is to be exposed to and comprehend political messages concerning that issue. People tend to resist arguments that are inconsistent with their political predispositions, but they do so only to the extent that they posses the contextual information necessary to perceive a relationship between the message and their predispositions. Given that these existing predispositions cannot be easily changed, any effort to influence opinions must be done in a way that aligns with and engages their deeply-held values to motivate concern and action— through values-based messaging. Values-based messaging uses clear, compelling short narratives that connect a person’s existing values to an issue.

The 6 principles of persuasion, which were first put forward by Robert B. Cialdini in his 1984 book “Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion,” are 6 principles that have been used for decades by businesses, politicians, and marketers alike, to influence people to do or care about something. The first principle is similarity, which is about trying to connect with people (as authentically as possible) in a way that they can relate to and identify with— this principle is all about safety in numbers, because people feel validated and are more influenced by something or someone they observe to be relatable or similar to them. The second principle is consistency: people want to commit to things that are aligned with their values, and people have a deep need to be seen as consistent. Once we have publicly committed to something or someone, we are so much more likely to go through and deliver on that commitment… and do it again. This can be explained, from a psychological perspective, by the fact that people establish a commitment as being in line with their self-image. Third, is authority: people really do have a tendency to believe someone they trust, or people who have authority. Whether it’s their mum, a local hero, a celebrity, or a politician, the average person will accept what a trusted figure of authority says without really questioning it. The fourth principle is consensus: put simply, people want to be part of the majority, not the minority. When we are surrounded by people who are all doing something, we want to reflect that. This is how trends spread so rapidly, especially in the age of modern technology and social media. Principle 5 is reciprocity; human beings are wired to basically want to return favours and pay back our debts and treat others as they’ve treated us. Finally, the 6th principle is scarcity: when people believe something is in short supply, or that they must act urgently, they want it more.

Storytelling is also a powerful tool to influence people’s opinions. Facts and figures are a great way to let people know about pressing global issues, and to help quantify the scope or depth of a humanitarian problem. But when you are trying to motivate people to care about an issue or take a specific action, telling a single story will have a far greater impact than any statistic. Evolution has wired our brains to be more receptive to storytelling. It has been one of our most fundamental methods of communication since the first cave paintings were discovered over 27,000 years ago. The science behind storytelling is pretty simple. Stories are, in their simplest form, a connection of cause and effect, and this is how humans think. When people make a decision about donating money or funding a project, most people do not rationally calculate the benefit they can expect from their contribution, they make intuitive decisions based on affective reactions. There are various studies that have explored what makes people act most generously, and the research has all confirmed that feelings, not analytical thinking, drive people’s generosity and compassion.

Mother Teresa once said, “if I look at the mass, I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.’’ When a story is told with an identifiable victim, it is much more likely to generate voluntary action than a number of unnamed “statistical victims.” This is referred to as the Identifiable Victim Effect. People pay greater attention and have stronger emotional reactions if they are presented with a case of an identifiable victim. People by nature are far less inclined to engage with a cause when they are presented with statistical data about multiple similar victims that are caught up in the same system of need.